Sea Disaster at Cellardyke Harbour

The Sea is a formidable master for those who make their living fishing and the rocks round Scotland’s shores add a particular hazard.

The inaccessibility of the Cellardyke harbour mouth in a storm was to blame for two local disasters.

1793 Tragedy

On the 23rd of September, towards the end of the Lammas drave, which was the time of the greatest harvest, seven local fishermen lost their lives as they attempted to enter the harbour during a storm. Only one of the crew, James Martin, survived after being swept towards the shore by a wave which deposited him on one of the skellies protruding from the sea. Fishing boats at this time were not decked and the inhabitants were open to the mercy of the elements.

1800 Tragedy

In a similar situation, a boat was seeking the shelter of the harbour in a storm, when it was overwhelmed by a terrific wave whichswept it towards the deadly reef – Skelly Point. Rudderless and disabled, the boat was crushed on the rocks while families watched helplessly from the pier. Seven of the crew sank beneath the waves in sight of the onlookers, but ironically, once again one of the crew was picked up by a wave and deposited on the same rock as the aforementioned survivor James Martin.

The story of William Watson’s survival became part of local folklore, when his wife Mary Galloway waded into the sea and helped him to the shore. The fact that he had thrown off his coat may have had something to do with his survival, as they were waterproofed with many coats of linseed oil, making them heavy. “I felt as if I walked on the water,” he later told his friends earning him the name “Water Willie”.

1875 East Neuk Disaster

On 18 September 1875, a great storm blew up on the whole of the east coast. Seventy-nine East Neuk boats were due to head home after the East Anglican herring season. The storm subsided overnight and on the morning of the 19th the fishermen set off for home. However, when they were underway, the storm suddenly blew up again and the boats were forced to scatter to seek shelter. Some headed for the Holy Island and others made for South Shields. Unfortunately, they did not all reach safety and two boats from Cellardyke and three from St Monans were lost.

The people of Kings Lynne, Norfolk erected a memorial to the 37 fishermen who perished in the storm.

The Cellardyke boats lost were the Janet Anderson, skippered by James Murray and the Vigilant whose skipper was Rob Stewart. The helm of the former was washed up at Cockburnspath but nothing was found of the Vigilant nor the 7-man crew of either.

Provision for Fishermen’s Families lost at Sea

When a boat was lost at sea, the practice of making up crews with relatives meant that many families could be left without any provision for their welfare. The two disasters at Cellardyke harbour left a total of 40 children fatherless.

The kirk- session and heritors of the parish, the latter including members of the Bethune and Anstruther families, as well as other landed gentry kept minutes of their meetings regarding the poor. Given the undoubted wealth of some of the gentry, they were prepared to give no more than 10/- towards a pauper’s coffin. They were were prepared to pay the rent of those in direst need however, and supply a grant to help clothe their children. The widows of men lost at sea figured prominently here.

Burgesses’ and Trades’ Poor Box Society of Anstruther Easter

In 1701 a group of local citizens and tradesmen set up a benevolent society to allocate money to the needy. Ministers and Town Councillors acted as referees for the widows in their appeal for funds to support their children. The society accrued funds, mainly by hiring out “mort cloths” to cover the crude wooden coffins of the dead. Made of velvet, these cloths were kept in a wooden box (hence the Society name), and charged for according to the size required (adult or child). Many widowed fishermen’s wives applied for this provision.

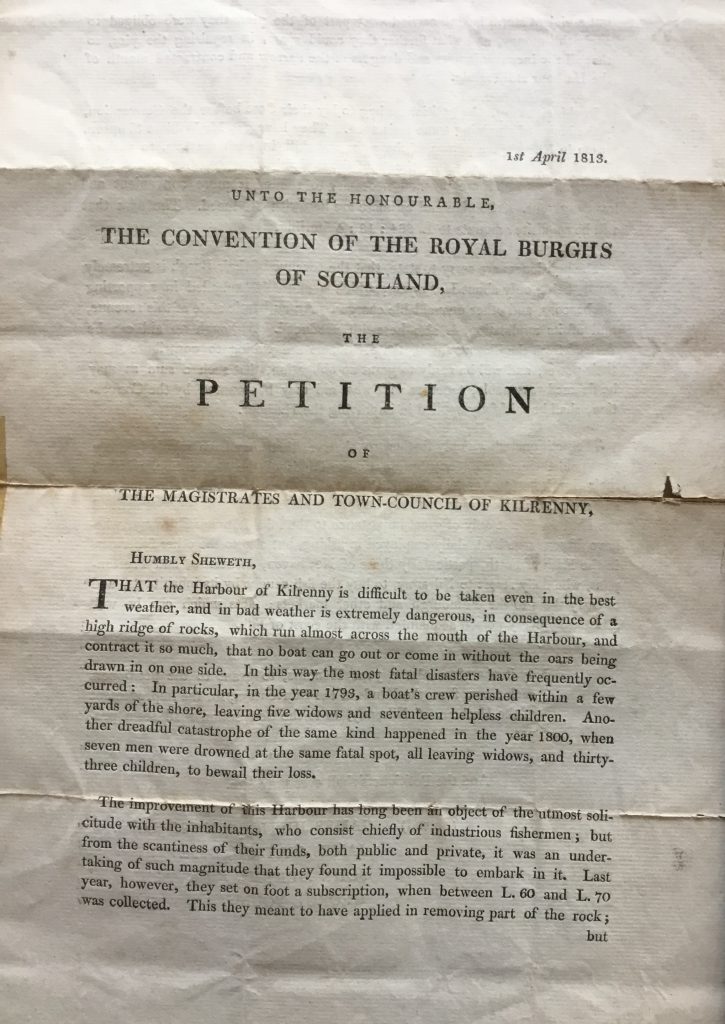

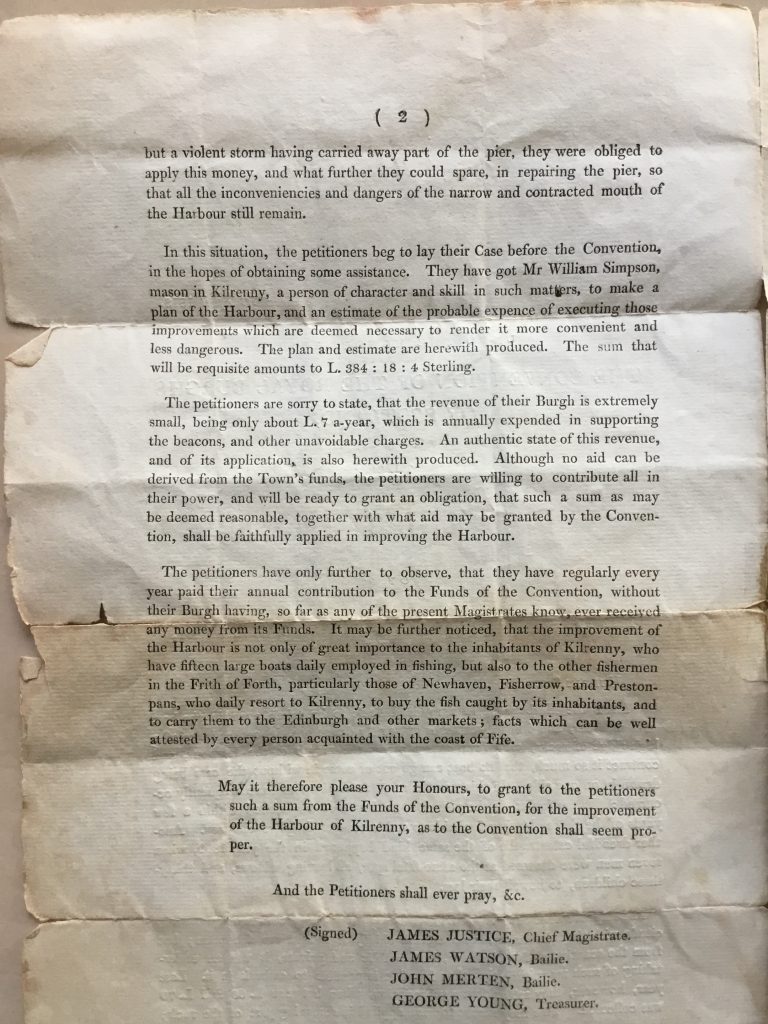

Petition for Harbour Improvements

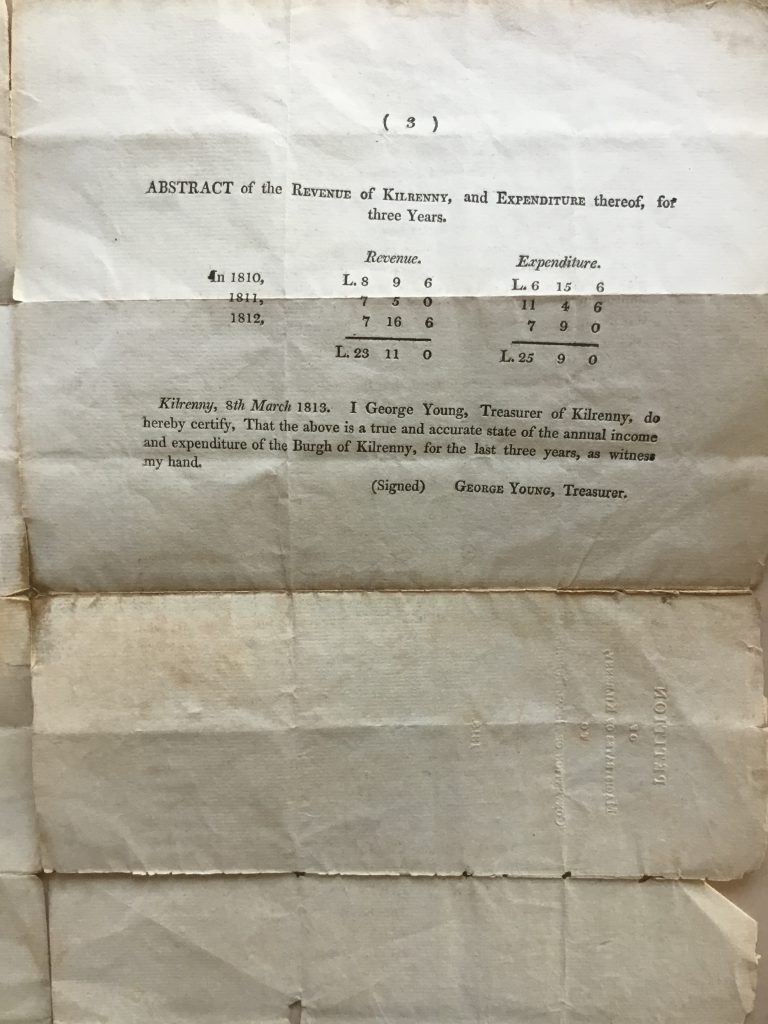

The aforementioned disasters within sight of the distraught families highlighted the dangers at the entrance to the harbour in a storm. In 1813 a petition to the Convention of Royal Burghs which was drawn up in 1813 described the ridge of rock outside the harbour which contracted the entrance so much, that the boat oars had to be lifted to allow entrance into the harbour. The fishermen had looked into having part of the ridge removed but damage to the harbour after a storm had swallowed up the scant funds they had collected. The petitioners requested funds from the Royal Burgh Convention stating that at present there were fifteen large boats fishing out of the harbour and it was also used by fishermen from other ports up and along the East coast.

The 1813 Petition of the Magistrates and Town Council of Kilrenny to the Convention of Royal Burghs

New Harbour at Craignoon

By the middle of the century the local fishermen were petitioning for a new deep-water harbour at Craignoon, a natural haven formed by a skelly, west of Cellardyke harbour (see map). Even boats safely moored within the old harbour could be destroyed in a gale, as they dragged their anchors and smashed against one another and the quay.

Money was collected for this purpose but an engineer’s report estimated the cost at £27 000, which was thought to be outwith the means of the fishermen of Cellardyke. In 1857 still determined, the plans were eventually killed off by the decision to build the Union Harbour at Anstruther which many of the Cellardyke boats had started to use because of the size of Cellardyke harbour.

Sources –

Kilrenny and Cellardyke by Harry Watson

Fisher Life 1879 by George Gourlay